Mental health disorders are on the rise, and consequently, so are medication prescriptions. Polypharm, the prescription of multiple medications, is rampant, as doctors and parents scramble to mitigate the distressing symptoms they witness in their patients and children. This is especially problematic in the United States, where the rates are nearly double that of other Westernized countries. Zito says, “Concomitant drug use applied to 19.2% of US youth, which was more than double the Dutch use and three times that of German youth.” (Zito, 2008. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric and Mental Health.) Increases in polypharm manifests concerning side effects, and can be quite debilitating to patients. Many doctors, clinicians and parents are seeking to expand their “treatment pie,” by utilizing a diverse toolbox for treatment beyond that of medication.

The US is distinct in that prescribing psychotropics medications to young people often is the first line treatment for mental health concerns. When the first medication is not effective, the next move is to add an additional medication in hopes of some amelioration. Let’s take the example of ADHD psychostimulant medications such as; Ritalin, Adderall, Vyvanse, Concerta, and Focalin. A child is struggling in school- unable to complete their school work, acting impulsively, and seemingly ignoring school rules. Doctors too often resort immediately to medications, and in turn, psychostimulants have the common side effects of suppressing appetite, inhibiting growth, increasing heart rate, causing anxiety, and contributing to sleep issues. When these side effects occur, doctors will often add another medication to help these symptoms. This is what we call polypharmacy; the simultaneous use of multiple drugs by a single patient, for one or more conditions. This is a slippery and dangerous slope.

A recent study, the Multimodal Treatment of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder Study (MTA Study) examined the efficacy of stimulant medication. The study initially showed promising conclusions, which were widely shared and used as a justification for increased production of stimulants and marketing by pharmaceutical companies. Looking more closely into the MTA longitudinal follow up studies, it was the concluded that longitudinal data did not support the use of stimulants. At the National Association of Therapeutic Schools and Programs (NATSAP) conference in January 2019, Keynote Speaker, Dr. Robert Foltz, presented on “Psychotropic Medications in Youth: Challenging the Assumptions that Guide this Practice.” And demonstrated the lack of longitudinal safety and efficacy studies for the most commonly prescribed psychotropic medications. “We had thoughts that children medicated longer would have better outcomes. That didn’t happen. There were no beneficial effects, none. In the short term, medication will help the child behave better, in the long run it won’t. And that information should be made clear to parents.” The MTA findings only support the short term (12 weeks) use of medication treatment, as there was a scarcity of data beyond that time frame. (Foltz 2019).

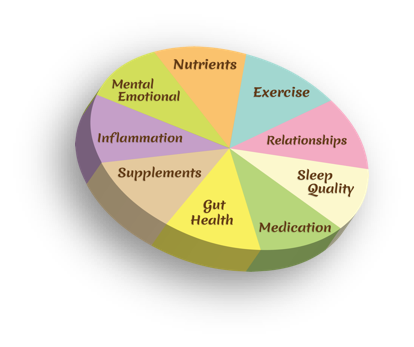

Dr. Britta Zimmer recently presented at the Hawaii Syncopate Doc Talks conference for physicians, and focused on the management of patients prescribed multiple psychotropic medications and how to discern medical necessity and improve safety within an outdoor behavioral treatment program. Dr. Zimmer did this with a series of case discussions while speaking to over 200 physicians on the topic. The core of the issue is that our children need an expanded scope, treatment providers who are willing to look beyond the use of polypharm psychotropics. As an Naturopathic Physician and Medical Director of one of the leading Integrative Psychiatric programs in the country, Dr. Zimmer suggest that doctors and parents examine their “treatment pie,” a range of treatments for enhancing mental wellbeing. Examples include improving nutrition, exercise, sleep, relationships, and mental/emotional health. A successful treatment plan is the sum of the parts of a whole. Britta Zimmer, ND, encourages people to read the MTA study and to diversify their treatment pie.